Explainer: What Howard Lutnick Said About India-US Trade Deal & Why New Delhi Calls It ‘Not Accurate’

US Commerce Secretary claimed PM Modi’s refusal to call Trump derailed bilateral trade agreement. India says the characterisation is inaccurate and that the two leaders spoke eight times in 2025.

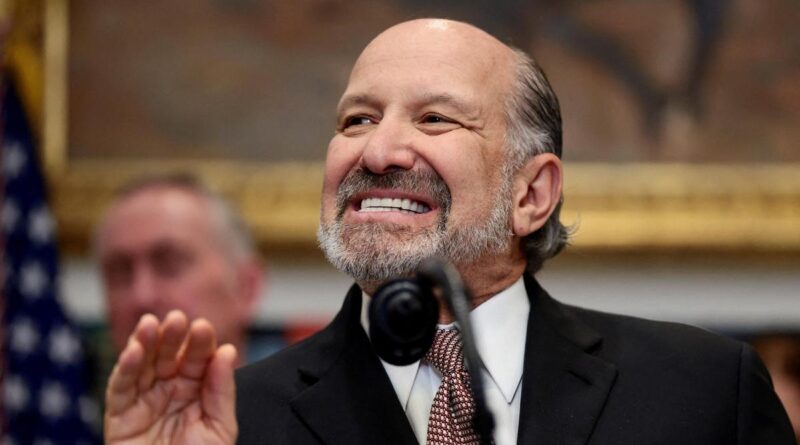

New Delhi: United States Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick has triggered a fresh diplomatic spat by claiming that a near-final India-US bilateral trade agreement collapsed because Prime Minister Narendra Modi did not call President Donald Trump to close the deal.

Speaking on the All-In Podcast hosted by American venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya on Thursday, Lutnick said the US had completed all technical negotiations but needed direct leader-to-leader engagement to finalise the agreement.

“I would negotiate the contracts and set the whole deal up, but let’s be clear. It’s his (Trump’s) deal. He’s the closer. He does it. It’s all set up, you got to have Modi call the President. They were uncomfortable doing it. So Modi didn’t call,” Lutnick said.

India swiftly rejected the characterisation, with the Ministry of External Affairs saying on Friday that the description of trade discussions was “not accurate” and pointing out that Modi and Trump spoke on the phone eight times in 2025.

The episode underscores the growing frustration on both sides over stalled trade negotiations that began with much fanfare in February 2025 but have since been overshadowed by Trump’s punitive tariffs on Indian goods and disagreements over India’s purchase of Russian oil.

What exactly did Lutnick claim?

In his podcast appearance, Lutnick laid out what he described as Trump’s “staircase” approach to trade negotiations, where countries that moved quickly received the most favourable terms while those that delayed faced progressively tougher conditions.

According to Lutnick, India was given “three Fridays” to close the deal and was expected to finalise its agreement before other Asian countries. However, when the deadline passed without the phone call from Modi to Trump, the US moved ahead with trade agreements with Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

“That Friday left, in the next week we did Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, we announced a whole bunch of deals,” Lutnick said.

He claimed these subsequent deals were negotiated at higher tariff rates because the US had initially assumed India’s agreement would be completed earlier. When India later approached Washington seeking to proceed with the original terms, Lutnick said the opportunity had passed.

“So now the problem is, that the deals came out at a higher rate and then India calls back and says oh okay, we are ready,” Lutnick said. “I said ready for what? You’re ready for the train that left the station three weeks ago?”

Lutnick suggested that India was now “on the wrong side of the see-saw” and “just further in the back of the line” for securing a trade deal with the US.

He added that Trump’s tough tariff stance on India stemmed from Modi’s decision not to engage directly. “India remembers the deal we agreed to. I remember it. They tell me you agreed to this deal. I told them I agreed then. Not now,” Lutnick said.

India’s categorical rejection

At the weekly press briefing on Friday, Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal firmly pushed back against Lutnick’s account.

“We have seen the remarks. India and the United States were committed to negotiating a bilateral trade agreement with the US as far back as 13 February last year. Since then, the two sides have held multiple rounds of negotiations to arrive at a balanced and mutually beneficial trade agreement,” Jaiswal said.

“On several occasions, we have been close to a deal. The characterisation of these discussions in the reported remarks is not accurate,” he added.

Jaiswal emphasised that India remains interested in concluding a mutually beneficial trade deal and stressed that Modi and Trump have maintained regular contact.

“Incidentally, Prime Minister and President Trump have also spoken on phone on eight occasions during 2025, covering different aspects of our wide-ranging partnership,” the spokesperson said.

The MEA’s response stopped short of directly naming Lutnick but made clear that India viewed his version of events as incomplete at best and misleading at worst.

The trade negotiations timeline

India and the US launched bilateral trade agreement negotiations in February 2025 after Modi’s visit to the White House. During that meeting, the two leaders announced plans to more than double bilateral trade to $500 billion by 2030 and pledged to negotiate a multi-sector bilateral trade agreement by fall 2025.

Modi committed to increasing energy imports from the US and reducing tariffs on American goods. India also agreed to purchase American fighter jets and offered concessions on products like bourbon whiskey and Harley Davidson motorcycles.

Between March and December 2025, the two countries held six rounds of technical negotiations. Indian officials offered a series of concessions including zero tariffs on industrial goods, phased reduction of tariffs on US automobile and alcohol imports, and fixed energy and defense purchases meant to narrow the trade deficit.

According to reports, Indian negotiators left talks in July with the impression that the two sides had agreed to a deal in principle. However, US negotiators considered India’s offers insufficient compared to deals struck with other countries.

A major sticking point has been agriculture. The US wants India to buy genetically modified crops and allow dairy exports, both of which face strong opposition from India’s domestic farm lobby, which wields significant political influence. India has held firm on excluding agriculture from negotiations with Washington.

The tariff war backdrop

The negotiations have unfolded against a backdrop of escalating US tariffs on Indian goods.

In April 2025, Trump announced sweeping reciprocal tariffs targeting countries with trade surpluses. For India, he imposed a 26 percent baseline tariff, though he suspended it for 90 days in April after countries approached the US to address trade issues.

The situation dramatically worsened in August 2025 when Trump imposed an additional 25 percent tariff on Indian imports as a penalty for India’s continued purchases of Russian oil, bringing total duties on some Indian products to 50 percent—among the highest imposed on any trading partner.

India denounced the measures as “unfair, unjustified and unreasonable,” asserting that its energy policy and supply chains are grounded in strategic autonomy.

Despite the steep tariffs, Indian exports to the US have shown resilience. After falling sharply to $5.5 billion in September, exports rebounded to $6.9 billion in November 2025, a 22 percent surge.

Why the phone call matters—or doesn’t

Lutnick’s emphasis on the need for a direct Modi-Trump phone call reflects the Trump administration’s preference for personalised, leader-to-leader diplomacy over traditional institutional channels.

According to a person familiar with the negotiations cited by Reuters, Modi could not have called Trump for fear that a one-sided conversation would put him on the spot, given that key issues like agriculture remained unresolved.

Political analysts say the episode reflects broader challenges in India-US trade relations. While Trump favours quick, transactional deal-making through personal relationships, Indian diplomats are more accustomed to negotiating through official channels and long-standing diplomatic processes.

“That structure has completely broken down in the United States,” Milan Vaishnav, director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told the Washington Post. “It’s really about who you know; what have you done for them lately? And kind of whose ear can you whisper into? That’s just a very, very different sort of diplomacy that has got India on the back foot.”

Moreover, Modi faces domestic political constraints. Being seen as capitulating to Western pressure—particularly through a personal phone call to Trump—could alienate his conservative base ahead of major state elections in 2026 and 2027.

Lutnick’s credibility problem

Lutnick’s latest remarks have drawn criticism within US policy circles, where he has previously been accused of overstating trade deals and mischaracterising negotiations, only for foreign governments to publicly correct his claims.

Several US officials have privately described Lutnick as a micromanager who struggles with the finer details of trade policy while projecting outsized confidence—a combination that has reportedly frustrated Trump and senior White House aides.

Critics have also noted that Lutnick’s account of the India negotiations contradicts his own earlier statements. In September 2025, Lutnick predicted that India would return to the negotiating table within “a month or two months” and would “say they’re sorry and try to make a deal with Donald Trump.”

That prediction did not materialise, and negotiations have remained deadlocked.

What happens next?

Both governments continue to signal interest in concluding a trade agreement, though the path forward remains unclear.

The Union government has indicated that a formal announcement could be made by March 2026 if negotiations progress. Such a deal could bring US tariffs on Indian goods down to 15-20 percent, significantly improving India’s competitiveness against rivals including China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

However, substantive differences remain on agriculture, tariff levels, and the scale of Indian commitments on defense and energy purchases.

India has also been diversifying its trade partnerships. In 2025, it concluded free trade agreements with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and New Zealand, and advanced negotiations with the United Kingdom, European Union, and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

The India-US trade relationship remains crucial for both sides. The US is India’s largest export market, and bilateral trade reached nearly $130 billion in 2024. For Washington, India represents a critical partner for diversifying supply chains away from China.

As negotiations continue, the Lutnick episode highlights the complex interplay of personal diplomacy, domestic politics, and substantive policy differences that will shape whether India and the US can bridge their differences and conclude a deal that both sides have described as mutually beneficial.