The Starstruck Surge: Why South India’s Film Idols Command Such Frenzied Devotion—and Deadly Consequences

From Silver Screen to Political Stage: The Deadly Devotion to South India’s Cinema Idols

NewsArc Bureau

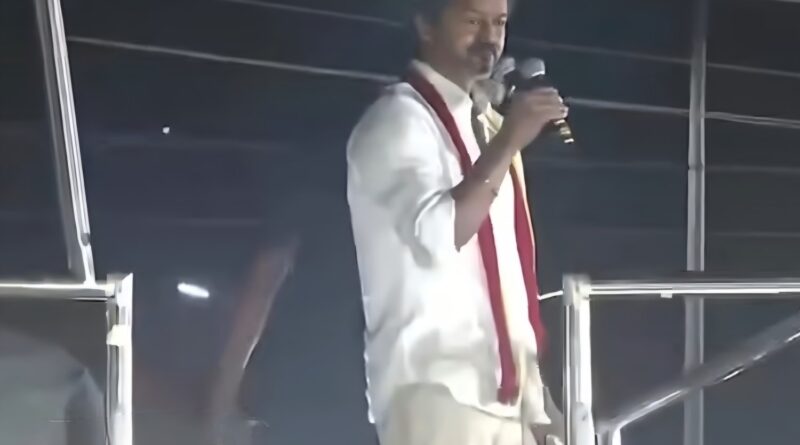

On September 27, 2025, tragedy struck in the bustling streets of Chennai, Tamil Nadu, as a massive crowd gathered for a political rally led by Thalapathy Vijay, one of South India’s biggest film superstars. What began as an electric show of support for the actor’s newly launched Tamilaga Vettri Kazhagam (TVK) party—a vehicle for his anticipated plunge into electoral politics—ended in horror. A stampede killed at least 36 people, including eight children, and injured over 50 others, turning jubilation into unimaginable grief.

The victims, many of them die-hard fans who had traveled from across the state, underscore a phenomenon as old as South Indian cinema itself: the near-religious fervor with which millions idolize their screen heroes. In a region where film stars aren’t just entertainers but cultural messiahs, Vijay’s rally wasn’t an anomaly—it’s the latest chapter in a saga of stardom bleeding into politics, often with explosive, and sometimes fatal, intensity.

To understand why South Indians—particularly in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and to a lesser extent Karnataka and Kerala—treat film icons like living deities, we must peel back layers of history, sociology, and cinema’s unique role in the region. Unlike Bollywood’s more nationalistic or escapist fare, South Indian films (Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam cinema) have long been intertwined with social reform, regional identity, and anti-establishment narratives. Dravidian politics in Tamil Nadu, for instance, emerged from a movement against caste hierarchies and North Indian dominance, and cinema became its megaphone. Stars, playing larger-than-life protagonists who topple corrupt systems or uplift the masses, embody these ideals off-screen too. Their fan clubs—highly organized networks that mobilize crowds for movie releases—morph seamlessly into political machines, turning applause into votes.

Economically and socially, these idols represent aspiration in a region where cinema is a rags-to-riches industry. Many stars hail from humble backgrounds, mirroring the struggles of their audiences: rural poverty, caste discrimination, and limited upward mobility. A hero’s on-screen triumphs feel personal, fostering a parasocial bond that’s amplified by limited media access in the pre-digital era. Today, social media supercharges it, but the roots run deep. As one analysis notes, “South Indian superstars had the intent and ambition to make it big in politics,” leveraging their charisma to bridge entertainment and governance. The result? A toxic brew of adulation that can tip into obsession, where a star’s word sways elections—and, tragically, crushes lives in the crush of crowds.

The Pioneers: MGR, the Eternal Savior

No figure looms larger in this pantheon than Marudur Gopalan Ramachandran—MGR to his legions. A matinee idol in the 1950s and ’60s, MGR wasn’t born into filmdom’s elite; he toiled as a supporting actor before exploding into stardom with swashbuckling roles in over 130 Tamil films. His on-screen persona? The chivalrous underdog: a Robin Hood figure dispensing justice to the oppressed, often laced with subtle Dravidian ideology of social equity. Films like *Naam Iruvar* (1947) and *Enga Veettu Pillai* (1965) weren’t just blockbusters; they were propaganda for progressive causes, scripted by allies in the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party.

By the 1970s, MGR’s fan clubs—numbering in the lakhs—were a shadow government, distributing food and aid in his name. When he broke from the DMK to found the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) in 1972, the transition was seamless. Elected Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu in 1977, he ruled till 1987, implementing welfare schemes like free school meals that echoed his reel-life benevolence. Devotees wept at his 1987 funeral; temples still bear his image alongside gods. MGR’s legacy? He proved stardom could govern, but it also sowed seeds of personality cults, where loyalty overrides policy.

Sivaji Ganesan: The Thespian Who Shaped the Stage

If MGR was the action-hero messiah, Sivaji Ganesan was the Shakespearean force of nature— a thespian whose emotive portrayals in epics like *Parasakthi* (1952) ignited Dravidian fervor. Ganesan didn’t chase the CM’s chair like MGR, but his influence was seismic. His breakout role as a downtrodden Brahmin railing against orthodoxy galvanized the anti-caste movement, earning him the moniker “Nadigar Thilagam” (King of Actors). Politically, he backed the DMK early on, using his clout to rally youth.

Ganesan’s fans weren’t just viewers; they were disciples. Riots erupted in 1967 when his film *Rajapart Rangadurai* was delayed, and his 2001 death drew lakhs in mourning processions rivaling state funerals. Though he flirted with politics via the Congress party in the 1980s (winning a Lok Sabha seat), his true power was cultural: He normalized cinema as a political tool, paving the way for successors. As scholars note, Tamil stars like him became “charismatic politicians” by blurring art and activism.

NTR: The Telugu Titan Who Stormed Hyderabad

Venturing east to Andhra Pradesh, Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao—NTR or “Natasimham” (Lion of Acting)—mirrors MGR’s arc but with a mythic twist. A Telugu cinema legend from the 1950s, NTR essayed Hindu deities in over 300 films, from Rama in *Lava Kusa* (1963) to Krishna in *Sri Krishnarjuna Yuddham* (1963). To rural Telugu audiences, he wasn’t acting; he *was* the god-king, blurring divinity with heroism in a state scarred by feudalism and poverty.

In 1982, at 60, NTR founded the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) on a platform of Telugu pride and welfare, sweeping to power as Chief Minister in 1983—ousting the Congress in a mere 30 months of campaigning. His yellow TDP scarf became a fan talisman, and his government’s subsidies for rice (at Rs 2 per kg) were straight from his reel populism. Fans deified him; statues proliferated, and his 1996 death sparked statewide shutdowns. NTR’s daughter-in-law, actress Lakshmi Parvathi, even briefly hijacked his legacy in a party split. As one observer quips, Telugu fans’ “wildest” devotion stems from stars’ tight grip on state identity and politics. His grandson, Chandrababu Naidu, still rules Andhra via TDP, a dynasty born of stardust.

Echoes in the Present: From Rajkumar to Vijay

This pattern repeats: Kannada icon Dr. Rajkumar’s 2000 kidnapping by forest brigands halted the state in grief, his moral authority swaying elections without him running. In Kerala, Mammootty and Mohanlal wield soft power through fan associations that double as social service wings. And now, Vijay—whose films like *Master* (2021) and *Leo* (2023) grossed billions, portraying anti-corruption crusaders—steps into the fray, his TVK launch drawing the fatal crowd. Like his forebears, Vijay taps into disillusionment with career politicians, promising a “people’s government.”

Yet, this craze has a dark underbelly. Fan wars turn violent—think the 2023 clashes between Vijay and Ajith devotees in Tamil Nadu—and rallies like last week’s expose crowd-control lapses amid unchecked hysteria. As stardom wanes in the streaming age, these icons cling to politics for relevance, but at what cost? South India’s star fever is a testament to cinema’s power to heal societal wounds, but when devotion stampedes over safety, it begs reflection: Are these heroes uplifting the masses, or merely riding their wave? In the end, the real tragedy isn’t just the lives lost—it’s the reminder that even gods can falter.